In my 20s, I had a habit of ending sex, often kicking guys out of my apartment, immediately after I came.

Because those instances were so long ago, and because of my past addictions to xanax, cocaine, and alcohol, only a collage of moments remain in my memory: the hurt look on a friend’s face as I dressed in the dark while he sat on his bed. Placing my hand on someone’s chest to stop them, saying, I’m tired, we should stop. Pushing someone’s hand away from between my legs after I got what I wanted, rolling over to drop into sleep, indifferent to whether they stayed or not. Their reaction was almost universal. Surprised by my sudden coldness, they quietly complied.

On one date, I met up with a guy I exchanged numbers with when I briefly met him at his job. We planned to have dinner and a drink nearby. When we met, he had deep bags under his eyes and appeared disheveled, unlike the collected person I remembered from when we met.

My shoe is broken. Can I drive your car to the restaurant?

He peeled the bottom of his shoe away from his foot as proof.

I looked at him hunched over on the pavement, losing his balance as he pulled the leather bottom away from his shoe. I thought his choice of footwear meant he imagined our date as a stationary one -- drinking at a bar -- where I imagined a long stroll in the late spring weather.

In that moment, I decided I didn’t give a shit if we were incompatible, if he were hungover or if I found his request to drive my car obnoxious. I told myself he probably knew how to fuck well, and quickly switched my fantasy from one based around the stimulating conversations I hoped for, to one centered on the sex we might have.

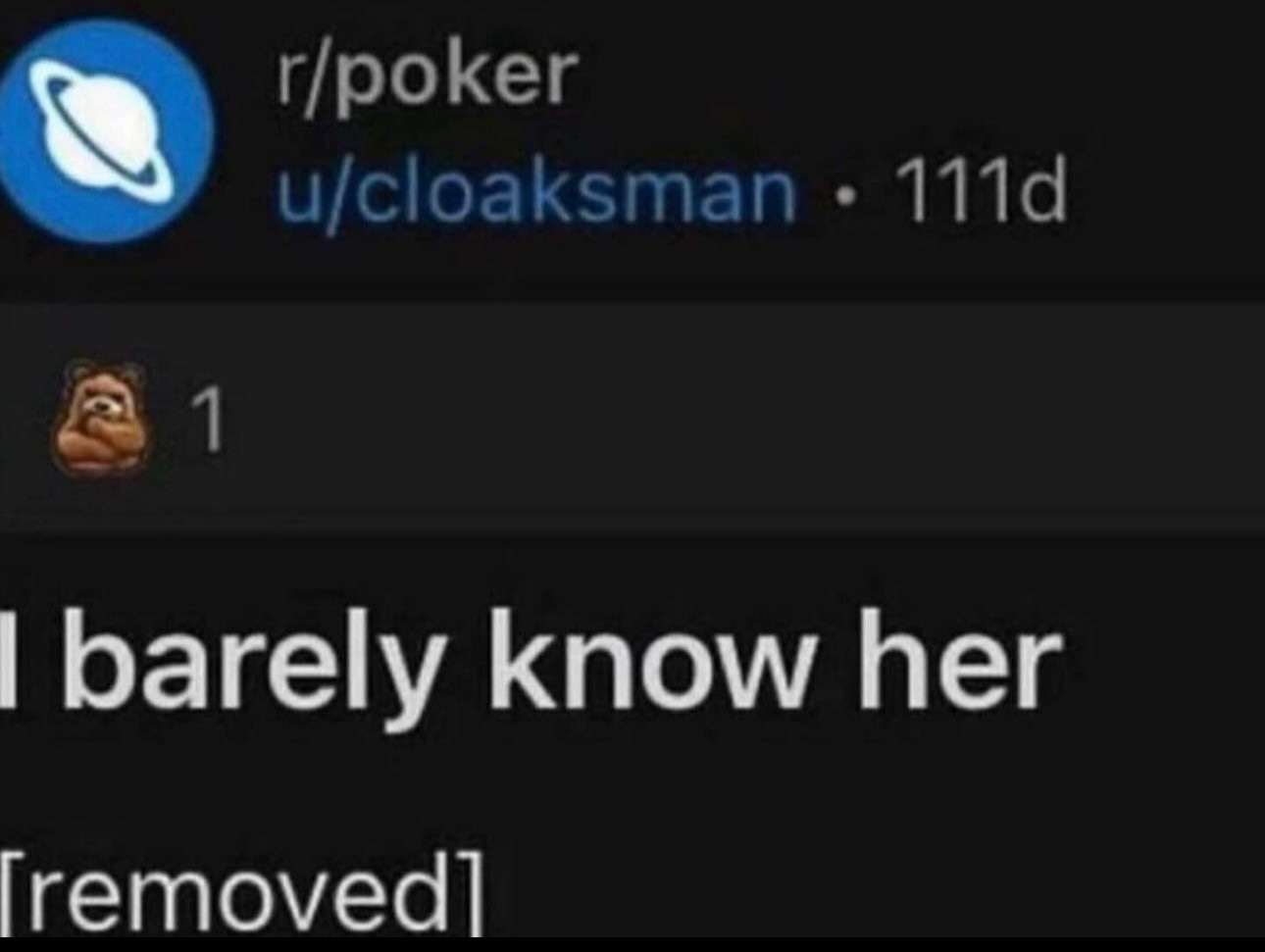

At the bar after dinner, her downed four drinks while I sipped one. He rambled about himself at length. To obtain my coveted nut, I would tolerate whatever stupid shit lie in the several hours ahead.

This will be our only date, I told him.

Come on, give me a chance.

When we entered my bedroom, I forged ahead. After a few clumsy minutes, I rolled away and went to sleep. I pushed his approaching face away early the next morning, said I was busy that day, that I had to get started.

But when we were texting you said you were free all day today.

I jumped out of bed and got dressed as a signal that he should do the same.

Moving into my 30s, I let people stay a little longer, sometimes the entire night. But recoiling in shame and ghosting them afterwards remained.

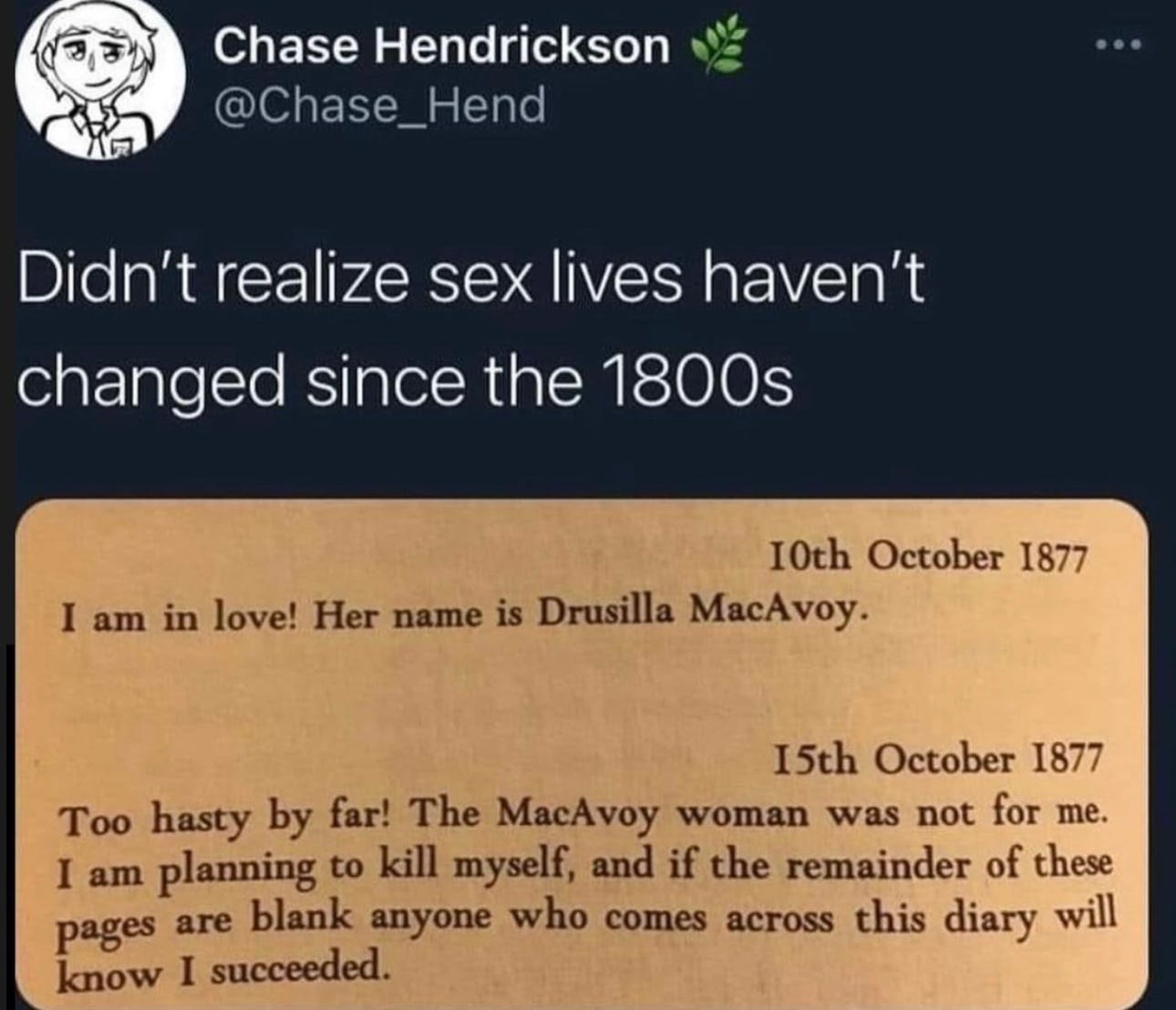

Since my late teens and into my 20s, I wrote detailed journals which I hoped to one day turn into a memoir. It wasn’t until I was sober and working with an editor, that I looked back on everything I wrote and noticed the passive voice I used in my journals.

I let him kiss me, I wrote of my first date with an ex boyfriend.

Distancing myself from my role in large parties or intimate dates by choosing only to record my attendance, I observed everything around me in a detached, aloof tone. Instead of writing what I thought or felt, I found it easier to observe details about who else was there, what they did, what other people said. I alluded to times I’d spoken, rather than writing what I’d said. Because I was afraid to acknowledge my desires, fears, and hopes, I focused on observing the world outside of me. Crafting myself as a passive, backseat character in my own life allowed me to keep what I then saw as a safe distance from the vulnerable act of doing.

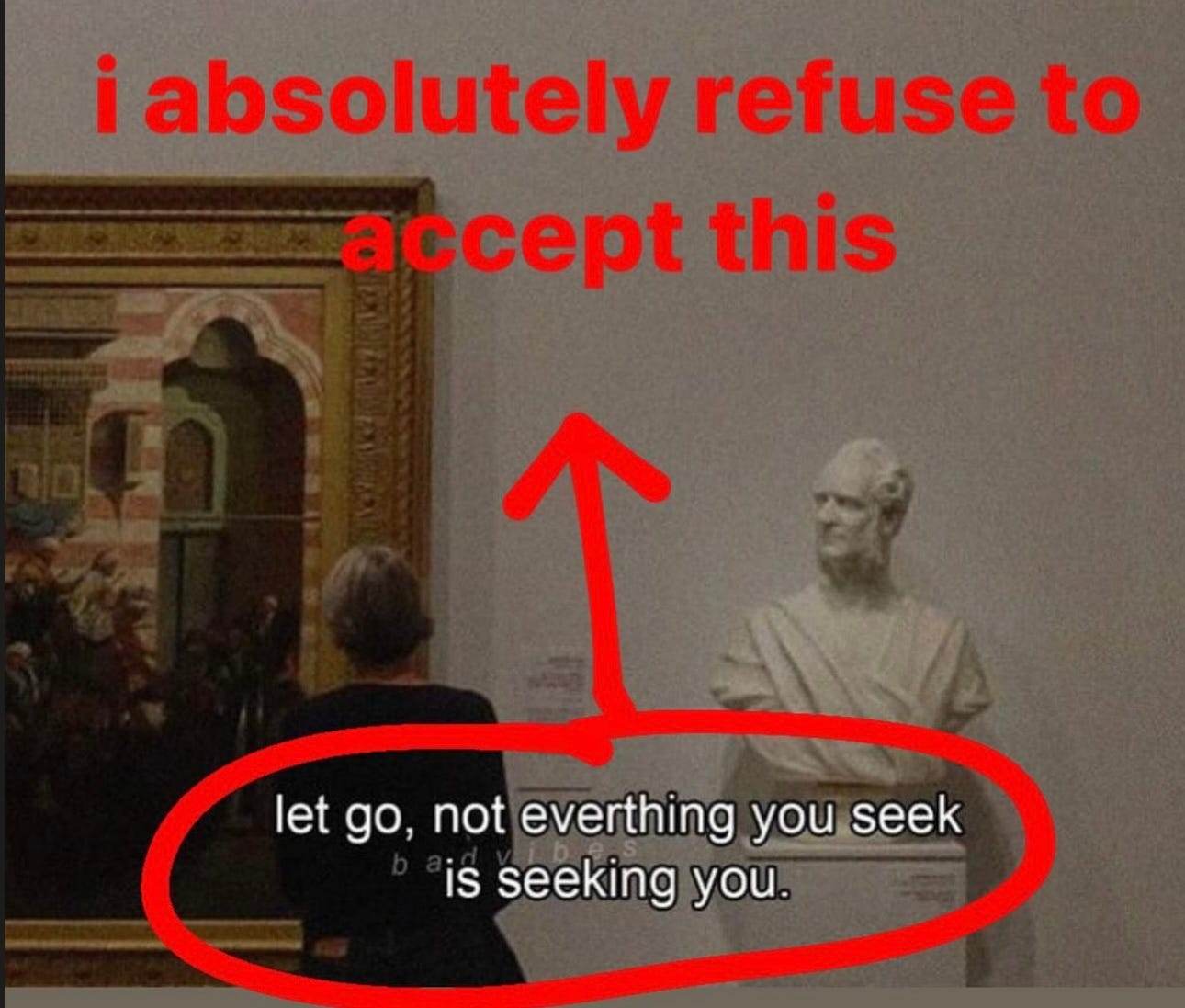

Because I acknowledged my emotions so rarely, when some latent desire or fear forced its way to the surface for air, I hardly recognized it. Unable to recognize what I wanted, let alone express those desires, sex was often a losing gamble. I didn’t tell the other person what brought me pleasure or discomfort, and later resented them for not knowing. I imagined the quality of casual sex I sought to be satisfying in every detail, the soft and careful way I imagined they kissed me, the intuitive way I wanted them to fuck me without telling them what I enjoyed. I imagined our bodies communicating in a language without words -- a deep biological knowledge activated. I imagined this connection, though temporary, would fulfill the desire for affection I couldn’t articulate.

I hoped to erase myself in sex — I didn’t want to perceive myself or the other person, only our bodies locked in furious struggle for pleasure. But the thinning fog of post nut clarity revealed myself unchanged: lonely, dissatisfied, confused about why I thought this interaction would benefit me at all.

To justify having sex with someone I had no interest in dating, whether a friend or stranger, I told myself another person would please me in a way I couldn’t do for myself, physically filling a void my hand or a bloodless piece of dick-shaped plastic could not. Masturbating bored me before it depressed me. Despite telling myself I was better off alone, I longed for human warmth. I imagined dick would temporarily stave off my loneliness.

Impatient to skip the performance of goodbyes and be alone, my body tensed as they dressed, willing them out, like if I strained hard enough they might disappear and save me the awkwardness of three more minutes together. I waited for the door to close behind them, for the relief of solitude to wash over me.

Like a drug addict telling myself this time it’ll be different, I struggled to recognize the cycle I placed myself in.

Despite the enormous walls I constructed, I blamed the other person for failing to connect with me.

I recently found my diary from 9/11, which records the day over five pages in a clinical tone. One week into my freshman year at Brooklyn Tech High School, the Twin Towers were attacked.

Standing with my classmates by my classroom window, I watched them burn. When a friend returned from the bathroom and whispered there was a better view from the bathroom window, I quickly asked for the pass, then hurried to see for myself.

I document the car ride home with my parents: sitting in traffic, spotting a cute guy on the street. Over two long paragraphs, I described making eye contact with him, about the smile he directed at me -- a slow, warm smile, not a fake corny one.

Now I have something else to remember from this day, I wrote.

Not documented in my journal was waiting in a long line of cars being directed by police at every corner, or my father’s shallow, hurried breathing. Frightened by his failure to catch his breath, my father’s panic created a self perpetuating loop of shorter and shorter gasps for air. He was hyperventilating.

Hyperventilating was a routine part of my father’s emphysema. His bedroom was lined with oxygen tanks, nebulizers, medicine boxes and drawers full of inhalers, for different times of the day and evening, some specifically for moments like this. From the backseat, I watched him fumble with the shirt pocket of his signature flannel, pull out an inhaler. He took a puff. Because he was stressed about the traffic, about the distance between himself and his medication, the unknown amount of time lying ahead before he reached them, his medicine was ineffective.

Cops at the intersection allowed cars to pass one row at a time with no regard for the light. My father wheezed as he pushed our car forward in line. When we pulled up beside the cop, my father rolled his window down. My mother spoke for him, asking could we please go ahead?

You can go ahead in an ambulance directly to the hospital or you can wait your turn.

The hospital promised chaos, not relief. On an average day, a day that was not 9/11, intake could take hours. Seeing a doctor, who would give my father the medication he already had at home, several more.

I didn’t personally know anyone who died on 9/11, but watching my father die during that time emotionally spent and cauterized me. I was an already-burnt match, incapable of sparking with new grief or shock.

That same year, I discovered and read Letters To A Young Poet, a compilation of ten letters poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to a young fan of his work. Rilke provides insight and advice on life, creating art, and love. In one letter, Rilke writes:

“A good marriage is one in which each partner appoints the other to be the guardian of his solitude, and thus they show each other the greatest possible trust. A merging of two people is an impossibility, and where it seems to exist, it is a hemming-in, a mutual consent that robs one party or both parties of their fullest freedom and development. But once the realization is accepted that even between the closest people infinite distances exist, a marvelous living side-by-side can grow up for them, if they succeed in loving the expanse between them, which gives them the possibility of always seeing each other as a whole and before an immense sky.”

At the time, I wielded the quote as a promise I’d always be alone. But in the back of my mind, it sparked hope: someday, someone might make eye contact with me across the great gulf of our solitudes, would see me for everything I didn’t know how to express but which I wished would be obvious to someone who loved me.

I wanted someone who saw I was flawed -- at times hypocritical and flighty, insecure and confused -- and who decided to stay.

During sex, I was hypersensitive. The guy didn’t even have to find my clit -- he could just fumble around close to it -- and the friction would make me cum, at which point I drowned in disgust. I often felt ashamed of myself for sleeping with someone I didn’t want to spend time with. My remorse intensified my resentment towards myself and, because I didn’t know where else to direct it, their presence.

A few months before I turned 18, in December of 2004, my father’s illness was so severe he struggled to walk across his bedroom. On an evening before he planned to visit his parents for a week, saving himself the drive back and forth, I went into his room to say goodbye.

See you when you get back.

When I turned to leave, he called my name.

Are you mad at me?

Why would I be mad at you?

For being sick.

His eyes filling with tears, my father looked at me. I’d never seen him cry.

Of course not.

That was the last time I saw him.

A year later, I met up with one of my closest friends to watch a movie in his room. I knew he had a crush on me when we were in high school, and, comfortable in his company, I felt in control. In his bedroom, some radar turned on. I wanted to be attracted to him; he was sensitive and kind. We appreciated the same music in the same way, laughing at the melodramatic lyrics and whiny vocals of emo bands like The Lindsay Diaries while unironically enjoying their music. We both understood there to be a little-appreciated but undulating magic in life, and walked around Brooklyn at night watching people’s apartment lights flicker off, sharing wonderment at the vast unknowable interiors of parallel lives.

I told myself fucking him might awaken deeper and stronger romantic feelings, like the dopamine release would compel me to date him. Being sad made me horny as fuck. Sex being the warm solution to my grief, everything I ever pushed down struggled to the surface of my being and reared its head as horniness.

Afterwards I felt only the desire to escape.

After I came, I remember leaving in the middle of the night as he sat confused and hurt on his bed. I was ashamed of myself for hurting him, for making our friendship a casualty. I knew fucking him was cruel, that subconsciously I had known it to be cruel even when convincing myself otherwise. I used him to temporarily alleviate my pain, to provide me with the illusion I was not alone.

I believed he knew me as a performance I put on, the “cool girl,” the easygoing girl -- the girl I learned to be in the hospital, watching my father die, where I learned expressing desire or fear ended in humiliation. Because I tried so hard to smother my own emotions, I didn’t realize I desperately wanted to be comforted. I could only reenact the end of a relationship I hadn’t wanted to lose, making myself the person who leaves before I was left.

In a 2018 article for The Washington Post, writer Anjali Pinto wrote about the way her grief manifested as a desire to engage in casual sex with multiple partners.

In the depths of my grief, I wanted sex and intimacy without having to date, compromise or be emotionally available to anyone new. I did not want to make small talk about my life as it was falling apart.

Anjali was 29 at the time of her husband’s death, with more lived experience than I had in high school and in my early 20s, and more in touch with herself.

Though I shared similar desires, I was unable to articulate them. I didn’t have language for “emotional availability,” or how I might become emotionally available -- the idea appeared to me as a threat of injury via abandonment. By fleeing or kicking someone out of my apartment, I remained in control, ending interactions in a predictable, reliable manner. I found the remorse or disgust washing over me post-casual-nut a preferable alternative to the sheer terror that someone I wanted to be around might not reciprocate.

Anjali writes that her “need for intimacy felt dire, like a big weight. The rush of feel-good chemicals created an overwhelming sense of happiness, even amid my loneliness.”

With every evening I spent pulling someone in just to push them away, I performed a small ritual that reasserted I would not be caught unprepared again. Though I saved myself from the risk of losing someone by being the one who leaves, I now recognize the pain I sought to avoid is the pain I may have created for men who could be grieving losses of their own.

I can imagine the loneliness must have been a massive void and the sex all drops of mist into that void, but some solace may be that some of the men were in it for the same? Your friendship casualty aside, of course.

In any case, it's unsurprising that the awareness of the compulsion did not lead to a change in behavior. I often find myself at a similar crossroad. Where I know I'm doing something detrimental, but cannot for the life of me stop regardless of wasted time or consequence.

I wonder what it would feel like to be ushered out of a party before I finished my drink is it were.

Feels like this is another piece of the puzzle.

As always, love the read.

As someone that has been on the receiving end of this sort of relationship structure, it's interesting to read an experience from the other side.